Fear & Greed – A Market Update

A look at market sentiment in the current environment.

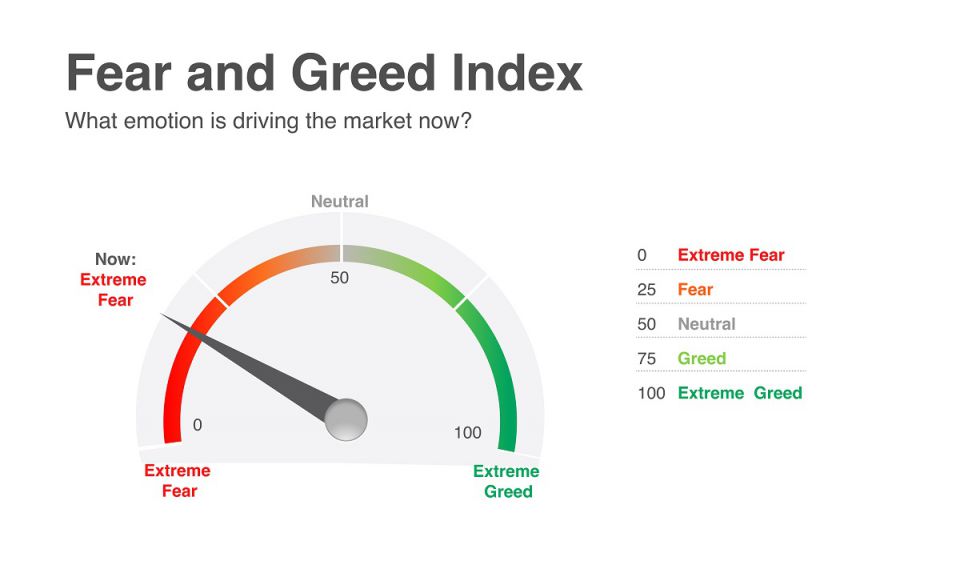

The Fear and Greed Index, published by our friends at CNN Business, is used as a barometer of market sentiment. The fundamental factors driving short term market movements are these two basic human moods, with markets tending to rise when investors feel greedy and fall when they fear fearful.

So, where are we now?

This current rating reflects the market turbulence that we have seen over the last month or so.

It feels like we have stuck in this Fear rating forever!

Not really. In fact, markets regained some of their poise during the summer, as you can see below:

These volatile movements are very common, as investor sentiment switches from positive to negative and back again, often over relatively short periods.

What on earth has been going on in the UK of late?

The latest edition of our market update has been held back for a couple of weeks, awaiting some end to the political fever currently gripping the UK. Since the last edition, we have had four Chancellors of the Exchequer and two (possibly three by the time you read this) Prime Ministers. Extraordinary times, indeed! Rather than calming the situation, Liz Truss’s appointment as the successor to Boris Johnson and the ill-judged budget has thrown the financial markets into turmoil, forcing a whole series of U-turns and what looks very much like the return of austerity.

Is it all the government’s fault?

Some of the wounds are, undoubtedly, self-inflicted. However, the wider picture has created a difficult backdrop, multiplying the negative reaction to the mini-budget, turning the promises of a new economic policy, Trussonomics, into fears that the government was playing Trussian Roulette with the UK economy.

What is the wider backdrop?

The invasion of Ukraine set fire not just to cities across that poor country, but also to inflation across the world, especially in basic commodities. This came on top of economies and prices that were already as the world – well, most of it outside China, anyway – emerged blinking into the post-Covid world. The reaction from Central Banks, especially the Federal Reserve in the US, has been to use the principal tool in their control to get inflation under control – they have raised interest rates quite aggressively. This has come as a shock to a world that had become used to the narcotic effects of almost zero interest rates for the last fifteen years.

Is inflation that serious?

Those of a certain vintage and with long memories will recall the pernicious effects of inflation. A high level of inflation erodes people’s purchasing power and, once it gets to a high level, can become self-feeding, with a spiral of higher costs feeding onto higher prices, leading to demands for more pay rises, which in turn feeds into higher costs. Deflation or zero inflation is equally unappealing and, since the Great Financial Crash of 2008, many of the activities of the monetary authorities has been dedicated to fighting this. After all, if prices are going down, why buy anything today if it will be cheaper tomorrow? Why invest in your business? This is why the principal job of Central Banks is to try to keep inflation within a target range. Typically, this might be around 2%, although I strongly suspect that they may need to broaden this definition going forwards.

What effect will interest rate rises have?

In general terms, higher interest rates act as brake on the economy, creating a higher bar to investment decisions and has a wider effect on spending, as it feeds through into higher mortgage rates. In the US, this is less of an issue as most mortgages are fixed for the lifetime of the mortgage, although it does mean that people find it much more difficult to move. In the UK, however, the effects are far more pronounced as, while a fair percentage of people have fixed rate mortgages for a limited period, the amount that they have to pay can rise very quickly. In the ultra-low interest rate environment, house prices surged and borrowings, as a multiple of annual earnings, reached historically very high levels. This level of borrowing is, then, likely to see house prices come under pressure as sellers find that buyers simply cannot afford to borrow enough to pay the price being asked. Add this on to the already sharp increases in energy prices – these have been capped, of course, but households will still be facing sharply rising fuel bills this winter compared to last – as well as inflation in food and the outlook for the UK economy looks challenging. This rise in the cost of borrowing does not just affect companies and individuals, of course, but governments too.

How are governments affected?

In the aftermath of the Covid slowdowns, government borrowing hit levels not seen since the second world war and this gap between government income and spending – the budget deficit – is funded by the government issuing bonds, which pay a fixed rate of interest each year and repay the capital in the future. These are colloquially known as Gilts, because of the perceived gold-plated guarantee of the UK government. At the beginning of the year, the government could borrow money for 40 years at around 1% but, with the rising interest rate environment and surging inflation, this had risen to around 3% by late summer. However, the new government’s first budget, which announced un-costed measures to help with the fuel crisis – increasing spending – and, at the same time, huge tax cuts to higher rate earners and companies – decreasing income - had a profound effect on the cost of the UK’s long term borrowing, with the interest rate soaring to almost 4.5%. This crisis of confidence in the UK as a financially stable country has already claimed its first victim, with Kwasi Kwarteng’s tenure as Chancellor of the Exchequer becoming one of the shortest ever.

What about the Bank of England?

With the need to slow down the economy to tackle inflation, the Bank of England has been in a very difficult position. Commentators have pointed out that the Bank of England putting its foot on the economic brake while the government presses on the accelerator was likely to see interest rates rise faster and farther than would otherwise be the case. Perhaps the appointment of Jeremy Hunt to the role and a reversal of some of the more adventurous proposals might reduce some of these pressures, but the Governor of the Bank has already warned of more rises ahead.

What else is needed to see inflation come down?

In short, what we really need to see is a resolution to the war in Ukraine. This, unfortunately, feels like a way off yet. Winters in this part of the world are harsh and not really ideal for military operations, so we are likely to see the stalemate continue until the spring. The reality, of course, is that there is unlikely to be a military resolution to the conflict as neither side is capable of knocking the other out. The solution has to be a negotiated settlement, but with both sides having such entrenched positions, it is hard to see how or when this will happen.

Inflation is just a measure of a rate of change. So, unless we see food and energy prices continuing to rise at the same rate – which we don’t – inflation should begin to moderate. This should, at least, pull inflation back down into single digits again in the UK, while the broader picture that I have talked about above should also see downward pressure on prices. However, inflation is unlikely to come back to the very low levels that we have experienced over the last fifteen years or so and, therefore, nor will interest rates. I think it highly unlikely that the 350-year lows in interest rates that we have just been through will ever be seen again, or at least not in our lifetimes.

Why has the pound been so weak?

Although the weakness of the pound makes great headlines – and there was certainly a short term drop to an historic low of 1.03 versus the US dollar in the immediate wake of the Kamikwaze budget – it has more been a question of the strength of the US dollar, rather than the weakness of the pound. Against the Euro, the pound currently stands at around 1.16 which is around the same kind of level we have traded at for some time. This dollar strength reflects both the absolute level of US interest rates – currently 3.25% but forecast to rise to 4.25%-4.5% by the end of the year – but also the safe haven of the US dollar at times of uncertainty.

What has all of this done for equity markets?

Interest rate rises have meant that the “risk free” return from cash deposits and government bonds has also risen. This, then, makes the relative attractiveness of equities – where profits and dividends can rise and fall – lower compared to the alternatives. In addition, companies who are at an earlier stage of their development – and, therefore, generating less cash, spending more money and making less profits – are also much less attractive relative to more established companies. Of course, rising interest rates can also lead to a wider slowdown and a recession, which can often be challenging for certain sectors.

A recession!?!?!

Recessions are defined as two quarters of negative growth, so it is not unlikely that some countries will move into a recession over the next year. However, recessions come in many shapes and sizes and not all, by any means, are the kind of collapse in economies and mass unemployment that feature in the popular imagination. In fact, recessions are a normal and natural part of the economic cycle and create room for new industries to emerge and for companies to reinvent themselves. While we see central banks, especially in the US, continuing to take robust action to bring inflation under control, we are reaching a point where we can see the brow of the hill ahead and, as ever, stock markets will continue to be a barometer reflecting the sentiment towards future expectations.

Do markets tell the future, then?

Global markets do not deal, particularly, with what is happening today, but rather focus on what is about to happen. The turbulence in equity markets reflects expectations that the economy will slow sharply next year, with or without a recession, but when we actually get there, markets are already beginning to look for the sunlit uplands of the next economic upswing. The fall in Gilts reflects a collapse in confidence about economic policy in the UK, even though that strategy had not been put in place. Unfortunately, confidence does not come in cans, so any recovery is going to be a relatively long, hard earned one and the “cost” to the UK is likely to hang around for some time. Nevertheless, a more sensible – dare I say traditional? – economic strategy will see some recovery.

So, should I be more positive, then?

As we have warned before, it would be a mistake to take the negativity that many feel toward the UK – and there is plenty to choose from at the moment – and project this internationally. The US economy is at a different stage of its economic cycle and is much more self-reliant. China has persisted with its zero Covid policy and mass lockdowns, but does not have the same inflation problems as Europe and the US. Perhaps the unique feature of this year has been the unidirectional nature of returns, in that equities and bonds have both fallen. This is very unusual – the last time that a move like this was seen was in the 1930s - as bonds, typically, tend to provide ballast to portfolios and help when markets are more difficult. However, despite the fact that interest rates will almost certainly continue to rise over the next few months, we are unlikely to see the kind of negative returns from these lower risk investments that we have seen over the year to date and they should return to playing their traditional, safe haven role.

Ultimately, investing in global markets involves taking a degree of risk. We can do the forensic work of ensuring that the quality of portfolios remains high and that we are invested in the kind of companies that will survive economic turmoil, but we cannot completely remove the volatility of the market which, roughly one year in four, will be down and, occasionally, substantially so. Indeed, the last twelve months have been the worst since 2008, but as we saw then and we will see in the future, while this is no guarantee that things will go up straight away, life goes on and companies providing the materials for modern life carry on too. As I always say, these companies – companies who own real assets, make real products which they sell for real profits and who pay real dividends to shareholders – have historically demonstrated their resilience in the most testing of times and are likely to do so in the future.

If you have any questions about the fear and greed index and how it could affect your money, please don't hesitate to contact us.

The above article and information was provided by RBC Brewin Dolphin